When WPF Modernization Becomes a Real Constraint in 2026

In 2026, WPF modernization is not driven by UI considerations. It becomes necessary only when the surrounding ecosystem starts to limit delivery, security posture, or operational alignment. Most teams evaluating WPF modernization already understand the framework; the question is whether the current WPF estate has become the bottleneck.

That bottleneck typically shows up as .NET Framework lock-in, third-party control stagnation or licensing risk, fragile packaging and update mechanisms, or persistent friction integrating with modern CI/CD pipelines and OS-level requirements. These are structural constraints, not cosmetic issues.

At the same time, when to modernize WPF is not a blanket answer. Stable, isolated, low-change internal applications that meet security and operational needs can continue running on modern .NET WPF without deeper re-architecture.

The right framing, then, is pragmatic: WPF modernization should be evaluated as a way to remove specific constraints. Anything positioned primarily as a UI refresh is already starting from the wrong premise.

WPF Modernization Paths and How to Choose Between Them

Once WPF modernization becomes necessary, the next question is not which framework is “better,” but which path resolves the specific constraints the enterprise is facing. Most failed WPF migrations start by comparing technologies in isolation.

Successful ones start by mapping constraints first, then selecting a target that minimizes risk while meeting long-term goals.

The available paths in 2026 are well understood. The challenge lies in choosing among them without underestimating what each option does and does not address.

Before selecting a modernization path, teams typically assess:

- Whether the application must remain Windows-only or support cross-platform delivery.

- How much functional UI parity is required versus tolerance for UX evolution.

- The depth of third-party control, COM, and native dependencies.

- Current and target CI/CD pipelines and packaging models.

- The expected lifespan and strategic importance of the application.

With that said, let’s take a look at the most common WPF modernization paths and how to pick the right one for you.

1. Modern .NET WPF (In-Place Modernization)

This path focuses on upgrading WPF applications to modern .NET while retaining the WPF UI model.

What it optimizes for:

- Lowest disruption to existing UI behavior

- Maximum reuse of existing XAML, MVVM patterns, and control investments

- Predictable migration timelines

What it does not solve:

- Cross-platform reach

- Fundamental UI or interaction model limitations

- Long-term alignment with non-Windows client strategies

Typical enterprise fit:

- Windows-only applications with heavy UI logic

- Systems with deep third-party control or COM dependencies

- Teams prioritizing stability and parity over reach

2. WinUI 3

WinUI 3 represents Microsoft’s modern Windows UI direction, decoupled from the OS and aligned with the Windows App SDK.

What it optimizes for:

- Long-term alignment with Microsoft’s Windows roadmap

- Modern Windows UI capabilities

- Cleaner separation from legacy WPF constructs

What it does not solve:

- Cross-platform requirements

- Parity gaps when migrating complex WPF UI behavior

- Maturity issues around tooling and ecosystem completeness

Typical enterprise fit:

- Windows-first products with a long runway

- Teams willing to absorb migration complexity for platform alignment

- Applications with manageable UI complexity

3. MAUI / Blazor Hybrid

Hybrid approaches combine native shells with web-based UI rendered through WebView.

What it optimizes for:

- Shared UI logic across platforms

- Web skill reuse

- Faster iteration on UI changes

What it does not solve:

- Deep desktop interaction parity

- Native control behavior equivalence

- WebView lifecycle and performance constraints

Typical enterprise fit:

- Applications with lighter UI interaction models

- Teams already invested in web stacks

- Scenarios where reach outweighs desktop fidelity

4. Avalonia

Avalonia offers a cross-platform, XAML-inspired UI framework targeting desktop environments beyond Windows.

What it optimizes for:

- Cross-platform desktop reach

- Familiar development patterns for WPF teams

- Avoidance of WebView-based hybrids

What it does not solve:

- One-to-one parity with WPF control ecosystems

- Vendor lock-in concerns

- Long-term roadmap certainty at enterprise scale

Typical enterprise fit:

- Desktop products with genuine cross-platform needs

- Teams willing to adapt UI layers

- Applications less dependent on proprietary WPF controls

5. Full Web Rewrite

A web rewrite replaces the desktop UI entirely with browser-based interfaces.

What it optimizes for:

- Maximum reach and deployment simplicity

- Centralized updates and distribution

- Alignment with cloud-first delivery models

What it does not solve:

- Desktop interaction parity

- Offline-first workflows without added complexity

- High rewrite cost and behavior drift risk

Typical enterprise fit:

- Workflow-driven applications

- Organizations standardizing on web platforms

- Scenarios where UI parity is negotiable

Choosing the Right Path: Constraint → Option → Risk

At an enterprise level, the decision typically resolves to how constraints map to risk. The table below reflects how architects evaluate WPF modernization options in practice.

| Constraint | Best-Fit Path | Primary Risk |

| Windows-only, heavy UI logic | Modern .NET WPF | Long-term UI evolution limits |

| Windows roadmap alignment | WinUI 3 | Migration complexity, tooling maturity |

| Cross-platform with web skills | MAUI / Blazor Hybrid | Behavior and performance drift |

| Cross-platform desktop fidelity | Avalonia | Control gaps, ecosystem maturity |

| Reach and distribution priority | Web rewrite | High rewrite cost, parity loss |

Regardless of the target path, successful modernization depends on how well the existing system is understood and constrained before change. Without that grounding, teams often discover too late that the selected option optimizes for the wrong problem.

Risk Reality: What Breaks, Why It Breaks, and Where Teams Underestimate Effort

Most WPF modernization efforts do not fail at compile time. They fail later (during validation, user acceptance, or production rollout) when subtle behavioral differences surface. This is why WPF migration risks are routinely underestimated: the application appears “successfully migrated” long before it behaves the same way.

In practice, breakages tend to cluster around a small set of repeatable patterns.

UI behavior drift:

- Changes in binding resolution due to differences in threading, lifecycle, or rendering order

- State inconsistencies when UI logic depends on legacy execution timing

- Issues that pass basic testing but fail under real usage patterns

Third-party control incompatibility:

- Gaps in feature parity between legacy WPF controls and modern equivalents

- Licensing changes or dropped support during modernization

- Control replacement introducing behavioral changes deep in UI logic

Hybrid and WebView instability:

- Version drift between runtime, WebView components, and host frameworks

- Input handling and drag-and-drop inconsistencies

- Lifecycle coordination issues between native and web layers, especially after framework updates

Packaging and update regressions:

- Breakage when moving from legacy installers to MSIX or similar models

- Changed assumptions around updates, rollback, and security boundaries

- Operational friction introduced post-deployment rather than during migration

Environment-specific failures:

- DPI scaling inconsistencies across devices

- Input and OS-level behavior differences not visible in development environments

- Failures that surface only after broad enterprise rollout

These issues surface late because modernization decisions are often made without a complete understanding of how UI behavior, dependencies, and deployment models interact in the existing system.

Certain modernization paths amplify specific risks: hybrid approaches tend to magnify behavioral drift, cross-platform frameworks expose control and parity gaps, and full rewrites carry the highest cost of rediscovering edge cases.

Teams that avoid these outcomes treat risk discovery as a pre-execution activity, not a downstream cleanup exercise. Instead of fixing surprises after migration, they surface fragile areas early, before committing to a path or scope.

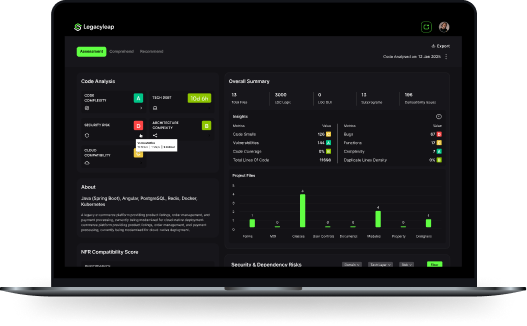

This is typically where platforms like Legacyleap are used: to expose failure modes ahead of execution, when sequencing and mitigation are still possible.

Executing WPF Modernization Without Losing Parity or Control

Once a modernization path is chosen, success depends far less on the target framework and far more on how the transition is executed. This is where many WPF initiatives stall because execution lacks discipline around sequencing, validation, and release safety.

Incremental modernization vs. full rewrite

In most enterprise environments, a full rewrite is the highest-risk option. It resets UI behavior, rediscovers edge cases late, and forces teams to re-earn user trust from scratch. An incremental WPF migration reduces that risk by allowing modernization to proceed in controlled steps while the existing system remains operational.

Incremental approaches typically succeed when teams:

- Modernize in slices rather than layers

- Preserve existing behavior while changing structure

- Defer irreversible decisions until risk is understood

WPF-specific sequencing realities

Incremental execution only works if sequencing respects WPF’s architectural realities:

- UI boundary isolation: Identify and isolate UI surfaces early. Mixing legacy and modern UI logic without clear boundaries is a common source of drift.

- MVVM drift control: MVVM patterns often degrade over time. Modernization exposes that drift. Without explicit correction, behavior changes accumulate invisibly.

- Interop containment: COM, native libraries, and platform-specific hooks should be treated as containment zones. Expanding their footprint during migration compounds risk.

Functional parity as a hard gate

Functional parity is not a best practice; it is a release gate. If parity is not continuously validated, behavioral differences surface only during UAT or production, when fixes are most expensive.

Effective WPF migration testing at scale focuses on:

- Behavior validation, not just unit coverage

- Regression detection across UI workflows

- Early detection of timing, state, and lifecycle differences

Parity validation must happen throughout execution and not as a final checkpoint.

Deployment readiness as part of modernization

Modernization is incomplete if the application cannot be built, tested, and released predictably.

Key WPF deployment modernization considerations include:

- Packaging choices: Legacy installers versus MSIX introduce different assumptions around updates, security, and rollback.

- CI/CD alignment: Builds and tests must run reliably across environments, not just on developer machines.

- Rollback and release safety: Modernized applications need explicit rollback paths to reduce operational risk.

These are not downstream concerns. They shape how modernization should be sequenced from the start.

Where Legacyleap Fits in WPF Modernization

By this stage, the pattern should be clear: WPF modernization succeeds or fails based on how well risk is surfaced before execution and how tightly behavior is controlled during execution. That is the gap Legacyleap is designed to address and the boundary of where it stops.

What Legacyleap is used for

Legacyleap is typically introduced once teams accept that modernization is unavoidable but want to avoid discovery-by-failure. Its role is not to replace architectural judgment or delivery ownership, but to make those decisions defensible.

In WPF modernization programs, Legacyleap is used to:

- Establish system comprehension: Build a concrete understanding of how the existing WPF application behaves, including UI flows, state handling, and embedded business logic, especially where documentation is missing or outdated.

- Map dependencies and impact: Identify third-party controls, COM/native interop, and hidden coupling that materially affect modernization feasibility and sequencing.

- Support modernization sequencing: Help teams decide what to modernize first, what to isolate, and what to defer, reducing the risk of committing early to irreversible changes.

- Enable parity validation: Support parity-first execution by making behavior differences visible early, rather than during UAT or post-release.

Across these areas, the value is predictability. Teams use Legacyleap to replace assumptions with evidence before scope, timelines, or paths are locked in.

Where Legacyleap adds the most value

Legacyleap is most effective in environments that match the risk profiles discussed earlier:

- Large, long-lived WPF applications with years of accumulated UI logic

- Systems with limited or unreliable documentation

- Heavy reliance on third-party controls or interoperability

- Modernization efforts must proceed incrementally without breaking production behavior

In these cases, the platform acts as a risk-reduction layer, surfacing constraints early and supporting controlled execution.

Where Legacyleap is unnecessary

Legacyleap is not a requirement for every WPF application.

Small, low-risk tools with:

- Minimal UI complexity

- Few external dependencies

- Clear ownership and documentation

…can often be modernized directly by experienced teams without additional tooling. Introducing a platform in these scenarios adds little value and unnecessary overhead.

Wrapping Up

WPF modernization is ultimately a confidence problem, not a tooling problem. Teams move forward when they can clearly articulate why a path was chosen, what is likely to break, and how functional parity will be preserved at each step.

This is where Legacyleap fits as a way to turn uncertainty into a plan. Try our $0 WPF Modernization Assessment to produce a concrete risk map, a feasible migration path, and a clear view of parity exposure before execution begins.

For teams that want to see the platform in action, book a demo for a practical view into how these insights are generated and used during real modernization programs.

Both paths serve the same goal: making modernization decisions with clarity, not optimism.

FAQs

WPF is still supported on modern .NET and continues to receive runtime and tooling updates. What’s considered “legacy” is not WPF itself, but long-running applications stuck on older .NET Framework versions, aging control libraries, and outdated deployment models. Modernizing WPF is often about removing those surrounding constraints, not abandoning the framework.

The earliest failures are rarely compilation errors. Teams usually see UI behavior drift first, such as binding resolution, threading timing, lifecycle differences, followed by third-party control gaps and packaging or update regressions. These issues surface late because they’re tied to runtime behavior, not static code structure.

A full web rewrite can be safer only when UI parity is not critical and workflows can be redefined without user disruption. For most enterprise WPF systems with dense interaction logic, incremental modernization is lower risk because it preserves behavior while changes are validated in controlled steps.

Functional parity has to be validated continuously, not at the end. This typically involves workflow-level regression testing, comparing behavior across legacy and modernized builds, and early detection of state, timing, and rendering differences. Platforms like Legacyleap are used here to surface parity gaps early and reduce manual validation during parallel runs.

Legacyleap is usually applied before and during execution. Teams use it to understand existing WPF behavior, map dependencies and control risk, and validate parity incrementally as modernization progresses. It’s most effective for large, long-lived systems where undocumented behavior and hidden coupling make manual planning unreliable.